Over the last decade, fintech has evolved from a label for plucky startups into a sustained movement that has disrupted the traditionally stodgy financial services industry. Much has been written about the success of fintech and how this wave of technological innovation has changed consumers’ lives.

But lost in all of the celebration of success and the billions of dollars in venture capital funding are the ideas that did not succeed. Over the last decade, many once-promising innovations failed and did not live up to expectations. It is important to not just celebrate success but also to learn the lessons from failure.

It is worth first defining how we are categorizing “failure.” This article is not focused on highlighting the demise of individual high-profile fintech startups that never justified their lofty valuations. Nor are we reviewing the various failed initiatives undertaken by large corporations, such as BloombergBlack or UBS’ SmarthWealth.

Rather, this piece will focus on fintech ideas that received some degree of initial hype and momentum, but ultimately did not live up to their promise. We will look at ideas that failed to go mainstream and change financial services in the way the founders originally intended.

Algorithm-based buy/sell/hold advice for investment portfolios

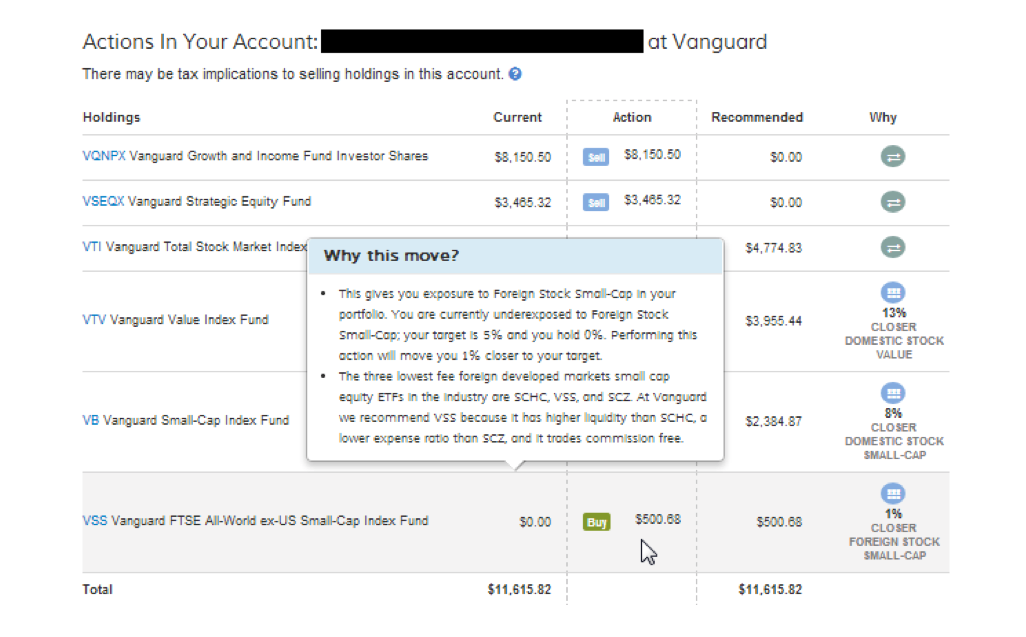

Several firms that would eventually be dubbed “robo advisors” started life as a fintech company that offered algorithm-based buy, sell and hold advice for a user’s investment portfolio. Customers would enter their usernames and passwords for their financial accounts, and these services would give holistic and specific advice for every single holding (e.g., sell this stock and buy this ETF instead).

This technology would help consumers improve their investment portfolios across all of their accounts irrespective of which institution it was held at. Below is a picture of what this looked like.

The technology was very impressive, but the idea did not go mainstream. Within a few years, the firms that offered this service (such as Financial Guard, FutureAdvisor, Jemstep and SigFig) had all pivoted to a different business model. According to Simon Roy, the former CEO of Jemstep, “the cost for no-brand startups to acquire customers who were both wealthy enough and willing to trade their own portfolios using our service was too high. We couldn’t find enough to make the economics work, and like everyone else, we pivoted.”

Tech and VC heavyweights join the Disrupt 2025 agenda

Netflix, ElevenLabs, Wayve, Sequoia Capital, Elad Gil — just a few of the heavy hitters joining the Disrupt 2025 agenda. They’re here to deliver the insights that fuel startup growth and sharpen your edge. Don’t miss the 20th anniversary of TechCrunch Disrupt, and a chance to learn from the top voices in tech — grab your ticket now and save up to $600+ before prices rise.

Tech and VC heavyweights join the Disrupt 2025 agenda

Netflix, ElevenLabs, Wayve, Sequoia Capital — just a few of the heavy hitters joining the Disrupt 2025 agenda. They’re here to deliver the insights that fuel startup growth and sharpen your edge. Don’t miss the 20th anniversary of TechCrunch Disrupt, and a chance to learn from the top voices in tech — grab your ticket now and save up to $675 before prices rise.

Why did the established giants of financial services not give their clients direct access to this technology? Since so many of the large firms offer their own proprietary mutual funds and ETFs, which an independent buy/sell/hold advice engine might recommend selling, the established industry was not interested in offering customers a service that could direct money away from the firm.

Thus, in 2023, the average online investment tool falls well short of services that were available a decade ago.

Peer-to-peer (P2P) lending and insurance

In the 2010s, P2P lending and insurance startups received significant attention. Firms like Lending Club and Prosper in the lending space, and Lemonade and Friendsurance in the insurance space, launched their businesses with a focus on the P2P model. This model promised a better experience and deal than receiving a loan or an insurance policy from a faceless corporation.

What happened? While these firms helped create a whole new category of online-only lenders and insurance providers, the dream of peer-to-peer arrangements going mainstream did not succeed.

To oversimplify, firms struggled to attract one side of the peer-to-peer model — the investors. Companies largely could not attract enough investors fast enough to gather the capital they needed. Many of these firms ultimately failed or pivoted to collecting capital from institutional sources, which is relatively easier than collecting capital from thousands of individual investors.

On-demand insurance and standalone financial planning apps

Over the past decade, both on-demand insurance and direct-to-consumer financial planning apps have had their moments in the sun. Dozens of standalone mobile apps were launched to help consumers plan and manage their finances. These apps were generally targeted at younger and/or less wealthy consumers who weren’t sufficiently affluent to qualify for a traditional financial adviser relationship.

On-demand insurance promised consumers thhe ability to buy a relatively small insurance policy on short notice — a one-off insurance policy for a 30-hour drive across multiple states, for example.

Both on-demand insurance firms and standalone financial planning apps have generally failed or pivoted. While these are different ideas, they failed for the same reason: overestimating the average consumer’s enthusiasm for personal finance.

Most people do not devote sufficient attention to their financial lives to remember to get insurance policies for special events. Likewise, companies learned the hard way that most people do not enjoy thinking about money or financial planning, and standalone apps struggled to keep users engaged and paying fees month after month.

In addition, over the last few years, the established financial industry has caught up, offering customers free financial planning and/or budgeting tools as part of their existing bank or brokerage account.

Trade-mimicking services

Over the last decade or so, at least 40 different fintech startups launched products offering consumers the ability to automatically copy the trades of top traders on their platform, top trading algorithms and/or to mirror the trades of top hedge funds, thanks to regulations requiring hedge funds to disclose their holdings on a quarterly basis.

There was some hype around the idea that such platforms could democratize finance, give smart traders an opportunity to shine even if they didn’t have Wall Street connections and help retail beat the market.

A decade on, however, most investors are not using some kind of automated trade-mimicking platform to invest their money. While many people look to friends and family for investing advice, the average consumer does not seem to be comfortable with following the trades of complete strangers.

As of 2023, investors seeking to outperform the market still primarily use large, established financial brands to manage their money. While BOTS and a handful of other trade-mimicking firms have been relatively successful, the model has yet to go mainstream.

Fintech can’t afford to forget the lessons from its first decade

There is nothing wrong with early failure. Pivoting to find product-market fit is a natural part of the startup lifecycle.

That said, it is important to remember what ideas did not succeed, and why, to avoid repeating the same mistakes. Looking across these four examples of fintech ideas that did not go mainstream, there are two main takeaways:

- First, fintech must remember that the average consumer doesn’t like thinking about money and often wants someone else to take care of it.

- Second, the industry must be realistic about the cost of client acquisition and how difficult it is to get consumers and investors to move money to platforms.

Entrepreneurs who will lead the second decade of fintech would be wise to learn the lessons from the past.